“Why Knowledge is No Longer Enough and the Importance of Science Communication”

July 2019

“Science has an important role today. Far more important for the future of civilization than I think it’s had at anytime prior to this moment.”

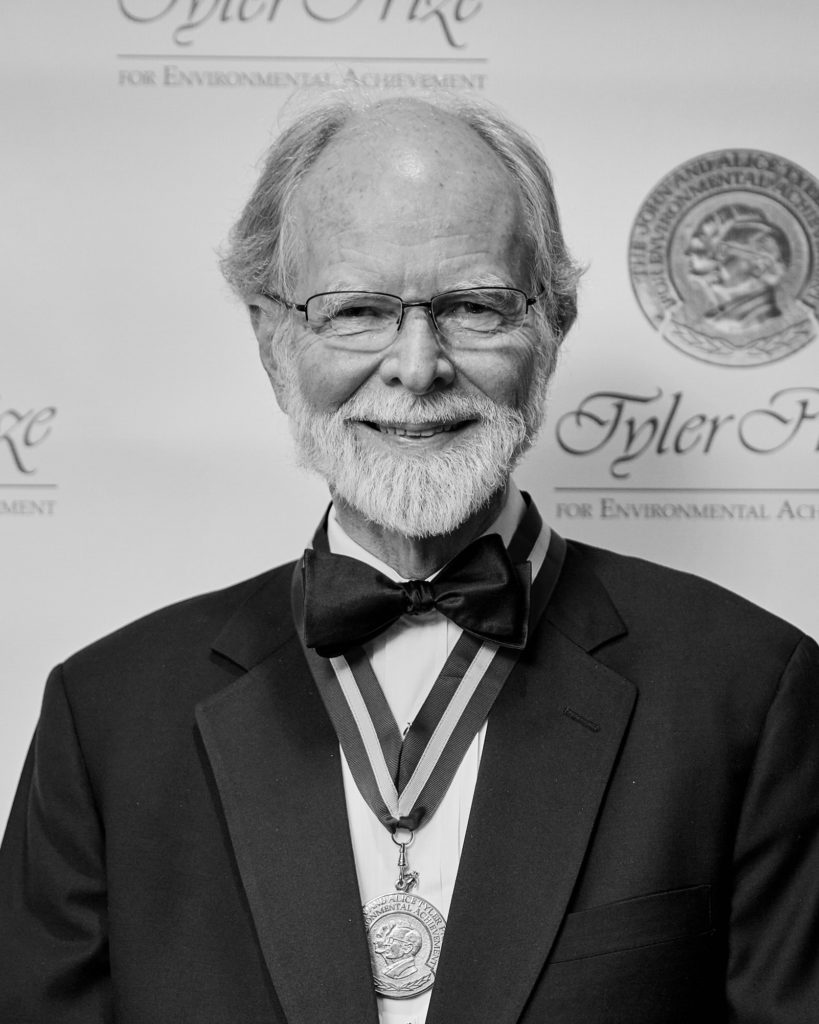

Dr. James (Jim) McCarthy, is a marine ecologist that has had an interdisciplinary career across environmental science and policy. Winning the Tyler Prize in 2018 and currently the Alexander Agassiz Professor of Biological Oceanography at Harvard University, McCarthy has fostered and led cooperative efforts among scientific disciplines to forge new, global-scale perspectives on environmental change. He has been at the forefront of synthesizing scientific knowledge about these transformations, translating science into climate policy. Furthermore, he has written for and been co-chair on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 2001 assessment on the impacts of and vulnerabilities to climate change, and continues to dedicate himself to producing and promoting the clear and effective communication of science for broader audiences.

Dr. James McCarthy, Photo by Christopher Michel

What is currently happening in your life right now?

I’m currently right at the end of my academic career. I have one more year in my professorship at Harvard, and I will be retired just a year from now. I’m spending this time preparing a textbook with a colleague that we’ve been working on for a few years. It’s an endeavor that has sprung from a course that we began teaching a little over a decade ago. He’s a terrestrial ecologist, and, of course, my expertise is in the marine realm, so we designed a course that we call Global Change Biology. We’ve been teaching that course here at Harvard and are now are working on a textbook that follows that same general template.

What is this textbook about and why is it so important to teach?

We look back very superficially over the last odd 100,000 years of Earth’s history, focusing on how climate, ocean, and biology has all changed. Then we move forward to the last 20,000 years, where coming out of the Ice Age brings dramatic changes, including the onset of the warming period.

The main focus, and where we look really intensely, is at the last 200 years. This is the period where human population has soared and we’ve seen massive transformations of land and ocean over that period of time. A lot of it due to the development of agriculture on land. The need for food to feed the world population, the need for fuel, the need for fiber. Plus the changing ocean ecosystems, as a direct result from unsustainable fishing and human interaction. It’s important that people are aware of this, because only once we understand what has happened in context, can we create real and tangible solutions.

What do you think is the future for humans 100 years from now?

Well, we have a pretty good idea as to how the Earth’s system works. That is the interactive parts of the climate, the atmosphere, the ocean, the biosphere, and the generation and consumption of these greenhouse gases by organisms in the soil, in the ocean. What we don’t have a good idea about is how humans are going to use this information.

It’s always been important to understand and take advantage of the advances in science. It led to technologies that brought humans out of poverty, cured diseases, made the longevity of humans what it is today because of better workplace conditions, better maternal health, better child health, cleaner water, cleaner air and so on. But the vision that led to those improvements were usually in the hands of a few people.

Occasionally the public will get riled up about something and create change. But today we had a very different situation where scientists are telling us that all of human society must act in an aggressive way over the next few decades to slow the rate of change. The climate is changing now more rapidly than ever before. Changing more than 10 times, maybe a 100 times faster than it ever did in the past, which means that you cannot adjust without enormous disruption.

A great example is sea level rise. When a sea level rise of one meter occurs over a thousand years, it’s hardly noticeable. Over a hundred years, it’s extremely disruptive. That’s the sort of change we’re seeing. The sea level could rise by one meter or more by the time my granddaughters are my age, and that’s a really startling realization.

So the future is not simply about how these natural processes unfold. The bigger sense is what humans will do. I think that’s a sort of really interesting moment in science right now where scientists have always observed, experimented, modeled and published papers to better understand the world around us. But now, we need to be at the forefront of making sure that information is communicated and available in such a way that actually leads solutions. Knowledge is not enough anymore, we need to ensure that the knowledge is being used.

We need to point towards solutions that the public can embrace and support in every way, from our political leadership to our financial investments, to slow the rate of change. Otherwise, humanity will be faced with an enormous disruption in all facets of society in the decades that will unfold within this century.

What can we, as a society, do to help reduce carbon?

There’s no vaccination, there’s no single invention. It’s a multifaceted problem. It ranges from all of our uses of energy and realizing that for many of them, there are ready substitutes that don’t have the same impact. For the U.S. it’s renewable energy, and if it hadn’t been for the investments made by the Obama Administration to get us moving on that, we wouldn’t be where we are today. No one 10 years ago would’ve guessed that today the state of Iowa would be getting almost 40% of its electricity from wind.

You see that this is being done because it’s cost effective. Because these investments by the administration through the Department of Energy, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), brought the cost of these innovations down. Batteries are more efficient and costing less. Solar is more efficient and costing less. Wind is more efficient and costing less. We can now generate, store and distribute electricity from renewable energy easily.

We need to consider all of our activities, from the personal up to through to corporate, and shift our behavior and actually consider the consequences of our actions. On a worldly level, not just as an individual.

It’s important for us to be optimistic and focus on what we’re doing right as a society, so what is something that you find encouraging?

It’s really encouraging to see for the first time, two things. Over the last couple years, there’s been a strong interest in climate change from the youth movement. We’ve never had that before. Secondly, we’ve never had a run up to a major primary with so many candidates talking about climate change.

However, climate change is not something that’s going to be the just the territory of the Democratic party. We’re now seeing a lot of Republican candidates express interest in advancing our nations’ commitment to climate change. Which makes sense, because it’s good for business. It’s only the fossil fuel business that is weakened by these breakthroughs in renewables. But we can’t forget that they’re powerful, have a lot of money and will fight it to their death, and we have to be prepared for that and work together to confront it.

Which audiences should scientists focus on spreading awareness about climate change?

Many scientists have been involved in helping the business community see opportunities to develop their business and investments while simultaneously helping the Earth. At then end of the day, businesses aren’t going to spend money where they don’t have to. So companies like Amazon, Walmart and Google have these big facilities where they invest more in wind and solar energy, because it makes more fiscal sense. They know it’s cheaper now, and they get a positive reaction from their consumers for taking action.

However, I think working at the public level is also really important. This is where we’re going to change the minds of people who are elected to office and serve in our state houses. A big challenge for scientists today, is that we have to do more than just write papers. We’ve got to share this information we’ve got to share it in such a way, that people, all people and not just scientists, understand why it’s important. We have to share it in a way in which people can use it to influence decisions. Decisions at all levels, whether they’re corporate heads, politicians, or individuals considering their utility options or next car.

What did it mean for you to win the Tyler Prize?

It’s hard to describe because it came as a big surprise. It’s such a distinct honor and nothing else that I’ve been honored for stands out like the Tyler Prize. Looking over the list of prior recipients, it’s a who’s who of all my heroes. Just to be in their company, it’s an awesome thing. I’m just enormously grateful to the committee and the whole process that they considered me to be of the same caliber of these very, very distinguished people. It’s just a terrific honor and I’m forever grateful.

July 2019

To read more on Dr. McCarthy’s work:

- Tyler Prize: 2018 Laureate Lecture

- Living On Earth Podcast: Tyler Prize for McCarthy

- Harvard University Press: The Sea, Volume 16: Marine Ecosystem-Based Management

- Research Gate: Climate uncertainties and their discontents: Increasing the impact of assessments on public understanding of climate risks and choices