A Conversation with Jane Goodall, Tyler Prize Laureate 1997

June 2021

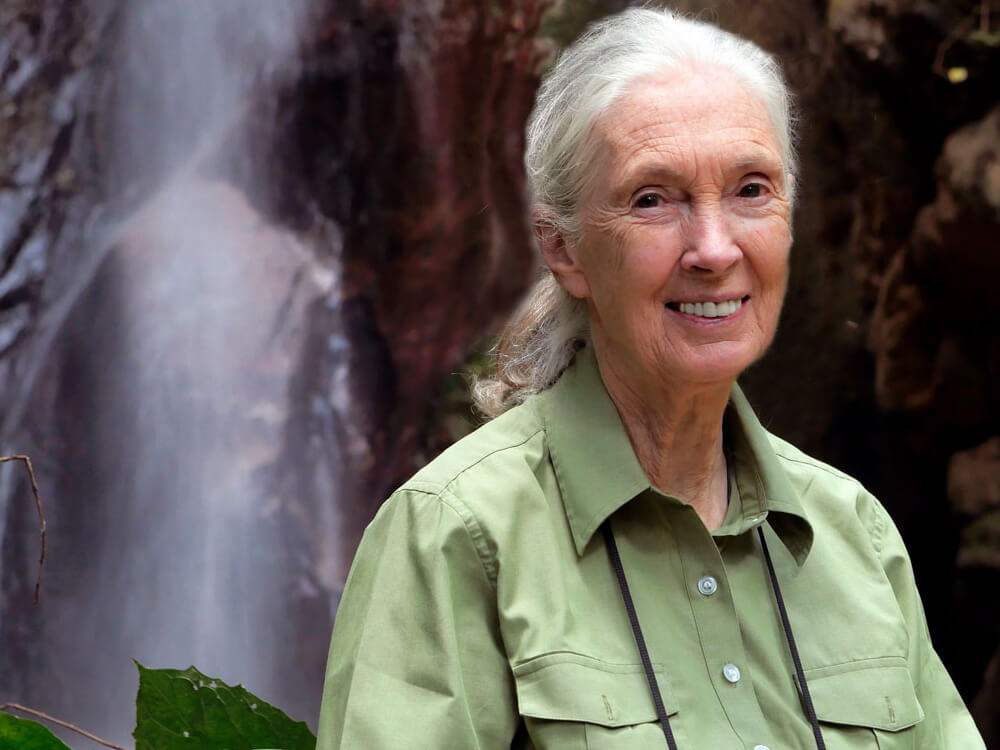

Dame Dr. Jane Goodall is a famous English primatologist and anthropologist, and the world’s leading expert on chimpanzee behavior and climate conservation communication.

Recognized with The Tyler Prize in 1997, she is the founder of the Jane Goodall Institute and the Roots & Shoots program, and she has worked extensively on conservation and animal welfare issues. She has served on the board of the Nonhuman Rights Project since its founding in 1996. In recent work, Dr. Goodall has just released ‘The Book of Hope’, has created a sustainably made and sourced wellness line in partnership with Forest Remedies, and a vegan Cookbook to promote plant-based diets.

Dr. Jane Goodall

It seems like you’ve been speaking everywhere this year, and one of the messages you’ve been strongly promoting is the concept of thinking and acting locally instead of globally. What inspired this message?

Well, in the days before the pandemic, when I was traveling all around the world all year long, I was meeting so many people – this is back in the nineties. I was just meeting so many young people that seemed to have lost hope. They were mostly just apathetic, not seeming to care much – and that’s still the same today. Some were really depressed – that’s still the same today. Some were angry – and that’s still the same today. I said, why do you feel this way? And they all said more or less the same: ‘you’ve harmed our future, and there’s nothing we can do about it.’

And so we have. If you’re one of those who think that older generations have harmed your future, we’ve been stealing your future for years, and years, and years, you’re not wrong. And is it too late? Is it true that there is nothing that you or they could do about it? I said, no. There is an opportunity to turn things around and to start healing the harm that we’ve inflicted to slow down climate change and biodiversity loss. What I realized is that so many people felt hopeless and helpless because they look at all the media and they see what’s happening around the world. They see the mess that we’re making and it’s awful. And we do need to know that. But at the same time, there are very many amazing projects going on around the world.

So what was I going to tell these young people? Well, ‘think globally, act locally’. Think, ‘what can I do here?’ Maybe it’s picking up litter. Maybe it’s clearing the stream of rubbish. Then you see you and your friends make a difference. All over the world, there are people just like you making a difference. When you get the cumulative effect of millions – hopefully billions – of ethical choices, then you dare to think globally.

Do you find that people are more hopeful or less hopeful now, compared to back then?

It’s a mixture. I can’t really say; some people are more hopeful. Some people are less hopeful. A lot of scientists have kind of given up, and others agree with me that we have this window of time. So it varies from person to person. But I will say that everyone involved in our Roots and Shoots Program – which is now in 67 countries and growing – are all very hopeful.

You are a big believer in all individuals making more ethically conscious decisions and purchases, however to be ethically conscious is often considerably more expensive. How can we lower this cost for more people to be able to do the right thing? What can people who can’t afford greener products do to help instead?

Well, it’s a major problem. It’s really a problem for economists rather than me. And it’s not an easy question, but it’s something that we have to tackle. Otherwise, the future is grim. But we have to do something to sort of readjust the balance between the rich and the poor. That’s something that I feel really strongly about. If we don’t alleviate poverty, we’ll never move on to the kind of world that we need. If we don’t reduce our own sustainable lifestyles – the rest of us – then the hope for the future is not good. So we have to do those things. It’s as simple as that.

I grew up in the war when every scrap of food was valued and it was all rationed; we had coupons. I think if it costs a bit more – say, organic and fair trade – you value it more and then you waste less. The problem of food waste is huge today. We’ve got to give a proper value to this cheap food. It’s only cheap because of the terrible wages that the people get in the factory farms, the ghastly conditions, the way the animals are treated – it’s cheap because of all that. And then genetically modified food, at the moment, is cheap. But actually if you grow food in a sustainable way, like permaculture or regenerative agriculture, or small family farms, then the price of these things, which is higher for fair trade or organic, will come down if more people buy it. And if the cheap food is valued correctly, then the well-made ethical food will actually be the cheaper one.

Then there is the cheap clothes – why are they cheap? Because of child slave labor. Because of sweatshops. It’s so unfair the way the world works at the moment and that’s the economist’s job. But I know how it should be. I just don’t know how to get there. That’s a question for the economists.

But currently, there are some people who, even if they’re going to value it more, they simply can’t afford it. So what can they do? I think what they can do is to try and leave as light and ecological footprint as they possibly can, where they can.

Often, youth are excluded from decision-making, and can only be heard through acts such as protesting. What advice do you have for the youth that want a seat at the table?

First of all, I think it’s very important that the youth that take a seat at the table are extremely well-informed. Hopefully they’ve had some firsthand experience and understand that to sit at these tables, they mustn’t demand. They’ve got to show that they understand the problem properly. And not just say, as I heard some young people say, ‘well, it’s wrong to fly, so we should stop flying tomorrow’. Well, you can’t. (We did through the pandemic, but that’s another matter.) You’ve got to be realistic. You can’t demand things that are actually impossible to do overnight. There has to be time. And so I think young people need to understand the need to think it through and ask themselves, well, if we demand this, how would they actually accede to our demands? And a lot of young people are just thinking how the world ought to be, which is fine, but don’t demand that what it ought to be without thinking through ‘how do we get there?’ In other words, just be realistic.

To be confrontational with people in power – I have found throughout my life – simply doesn’t work. You want people to change from within. They’re not stupid or they wouldn’t be where they are. They understand how the world is wrong, they really do. But how do you reach the heart? Well, I reached the heart with storytelling and young people can reach the heart with storytelling too.

I know a lot of young people change the heart of their fathers, their grandfathers, by telling stories about what’s happened to them and how they feel about it. A story of going to a place and seeing that devastation caused by some big giant corporation.

Your book, Book of Hope, has just come out, and you have listed 4 key reasons to hold onto hope, “The Amazing Human Intellect, The Resilience of Nature, The Power of Young People, and The Indomitable Human Spirit.” Over the years, have you ever witnessed anything that has made you want to give up hope? What has kept you hopeful?

First of all, I’m an extremely obstinate person. I’m not going to give up. I don’t give up. I’m not willing to give up. By the way, I should intersect here that it’s always really important to listen to the person who disagrees with you. The person you’re angry with. Because maybe there’s something about that that you need to learn from.

So yes, I felt angry. Yes, I felt frustrated. Yes, I felt depressed at times. But on the other hand, I’m not going to give up. And the media pays so much attention to the doom and gloom, which we need to know about, but I’ve had the advantage of going all around the world and I’ve met so many amazing, incredible people. Some with well-known names like Vandana Shiva in India, and some people who are just quietly getting on and doing it and making a difference.

One example is two men in China; one is blind and the other has no arms. And for some reason they paired up. They came from the same village and they started talking about how the village was when they were young, with birds and trees. There had been some devastating agriculture and the trees had gone. And so they thought, ‘oh we’re going to make our village beautiful again’. These two, with no funding, planted 10,000 trees between them! First of all, they did it wrong and all the trees died. But they didn’t give up, and the following year – they did it differently. It’s amazing to watch them.

So, we need the media to give more space to the hopeful stories because it’s when people read the hopeful stories that they become hopeful. ‘Well, if he did it, I can do it.’ And that’s what we need. Because if you lose hope, then give up, are you going to bother to pull the trash out of the stream? If you feel it’s not going to make any difference? Not unless you’re forced to. What’s the point? But if you think, ‘yes, I’m going to do my bit and they’re doing their bit, yes, we can make a difference’. We need hope. And hope generates hope. The more hopeful you are the more hopeful the people around you will be.

Finally, considering all of your career, what are you most proud of?

Two things, actually. One is when I first went to Cambridge University after being with the chimps for one-and-a-half years; I had not been to college at all. I had no degree. But my mentor Louis Leaky insisted I had to get a degree or else I’d never make money. And I had never been taken seriously, but there was no time to mess about with a BA. He got me a place in Cambridge to do a Ph.D. in Ethology – I didn’t even know what Ethology was, as I’d never been to college. I was extremely nervous. It was there that I was told I’d done everything wrong: chimps should have had numbers, not names; that wasn’t scientific. I couldn’t talk about personality, mind, or emotion – that was unique to humans. Well, I knew they were wrong because my dog taught me when I was a child. And so thanks to my wonderful supportive mother who told me I should have the courage of my convictions, I just went quietly on writing about the things the way they actually are. Gradually the scientists had to come around and admit that we humans are not the only beings on the planet with personality, mind, and emotion. So began this change. And if you look around the world, more and more respect is being given to animals as more and more people understand they’re sentient. And so that’s something that chimps helped me start.

Secondly was starting Roots and Shoots. Encouraging youth to participate and engage in solving our climate crisis to spread hope.

June 2021

To read more on Dr. Goodall’s incredible work:

- Facebook: @janegoodallinst

- Jane Goodall Institute

- Roots & Shoots: https://www.rootsandshoots.org/

- National Geographic – Jane Goodall