My Work Helped Save Cheetahs From Extinction. Who Will Save The Other Species?

As COP16 Unfolds In Colombia, A Veteran Conservationist Speaks Out

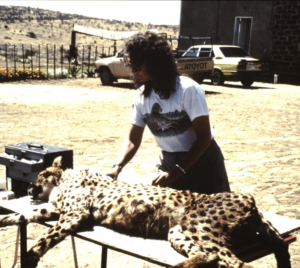

By Dr. Laurie Marker, 2010 Tyler Prize Laureate

When I moved to Oregon to open the state’s third winery in 1974, my plans to become a viticulturist got derailed by a cheetah cub named Khayam, whom I met at my side job working at a drive-through animal theme park called Wildlife Safari.

I hand-raised Khayam and loved her dearly. In 1977, Khayam and I traveled together to Namibia in Southern Africa to participate in the first rewilding research project aimed at evaluating whether a captive-born cheetah could be taught to hunt. Both Khayam and I learned to hunt in Namibia. While we were there, I learned that local farmers were killing hundreds of cheetahs annually in an effort to protect their livestock. During the next decade over 8,000 cheetahs were eliminated from the Namibian landscape.

When I returned home to Oregon and subsequently Washington, D.C. to share my findings and sound the alarm, I realized there wasn’t any organization or team assigned to saving the world’s fastest land animal from extinction. Most of the big money was being spent on the large megafauna, like elephants, rhinos, and tigers. As a former goat farmer and member of Future Farmers of America myself, I knew enough about farming to talk to these farmers and find out what was prompting them to kill so many cheetahs. Were they really losing that much livestock to cheetahs, or was it more of a perceived threat? Maybe I could work with them to find solutions to the challenges they were facing.

In 1990, the first year of Namibia’s independence, I started the Cheetah Conservation Fund and moved to Namibia permanently to develop an International Research and Education Center on a 156,000-acre private wildlife reserve.

Today, the center boasts a modern genetics lab, a registered veterinary clinic, a biomass research & production facility, a model farm with livestock-guarding dogs, a goat milk creamery, and an eco-tourism operation that’s open to the public. The center employs hundreds of people in one of Africa’s most economically challenged countries.

In the five decades I’ve spent researching cheetahs, I’ve learned about the critical role top predators play in maintaining biodiversity. While many of our conservation strategies historically have focused either on protecting a specific species or conserving areas of land, a more integrated approach combines species-centric and area-based strategies. This yields better results.

Iconic, charismatic animals like cheetahs serve as umbrella species, meaning their conservation helps protect a wide range of other species within the same habitat. Conservation of the large landscapes that cheetahs need to thrive is part of this umbrella strategy. Smaller organisms are fundamental to maintaining the balance of ecosystems: the cheetah needs them all, and they need the cheetah.

As we prepare for the upcoming UN conference on biodiversity, COP16, themed “Peace with Nature,” there’s an opportunity to take concrete actions that make a real difference. “The added value of holding COP16 in Colombia lies in our vision of Peace with Nature and in recognizing that the true struggle of the 21st century is for life,” according to conference organizers.

This aligns with the ideals of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, a landmark agreement adopted in December 2022 aiming to halt and reverse the loss of biodiversity by 2030 through goals such as restoring 30% of degraded ecosystems and reducing extinction rates tenfold by 2050.

Agreements and frameworks like these give us a roadmap, but it’s up to each of us to ensure our efforts don’t fragment into isolated initiatives. Conservation can’t just be about saving one charismatic species or conserving untouched land – it must be about systemic change that benefits all life, from apex predators like cheetahs to the tiniest microorganisms that form the bedrock of ecosystems.

If we manage to transform our relationship with nature, adjust our production and consumption practices, and ensure that collective actions promote life instead of destroying it, we’ll be addressing the most important challenges of our time.

For my part, I have dedicated my life to not just the cheetahs, but the people and wildlife that share the cheetahs’ landscape. But you don’t have to make the commitment I’ve made in order to make a difference. Just like the parts of the landscape coming together to form a balanced ecosystem, each of us can contribute in our own way to create lasting change.

Whether it’s supporting conservation organizations, making sustainable choices, or raising awareness, every action counts. Together, we can ensure that the intricate web of life—from the majestic cheetahs to the smallest soil organisms—continues to thrive.

The power of collective action is immense. If we all play our part, we can build a future where people and nature coexist in harmony.

Click here to learn more about Dr. Marker and her tireless work with the Cheetah Conservation Fund.