The Battle Against Greed and Corruption to Defend Our Valuable Wetlands

March 2022

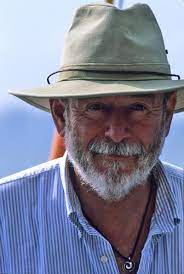

Exequiel Ezcurra is a plant ecologist and conservationist, and a member of the Tyler Prize Executive Committee, responsible for selecting the Tyler Prize Laureate each year.

A Professor of Plant Ecology at the University of California Riverside. Dr. Ezcurra is known for translating scientific research into tangible, positive conservation outcomes. His work has influenced policy at the highest levels of government. It has also created strong and lasting collaborations between the governments of Mexico and the United States. His highly interdisciplinary work spans desert plant ecology, mangroves, island biogeography, sea birds, fisheries, oceanography, and deep-sea ecosystems.

Dr. Exequiel Ezcurra

We know that wetlands’ ecosystem services are worth so much, yet they’re still being destroyed. Do you think the concept of Gross Ecosystem Product, ecosystem services, and the value of nature (a la 2020’s Laureates Gretchen Daily and Pavan Sukdev) is only just now dawning on humanity?

First, The concept is fairly new and it takes a while to dawn on the human collective consciousness, the importance of these ecosystems. Previously, there was a law that prohibited the destruction of wetlands for development. Coastal developers and hotel developers were trying to topple down the law, arguing that coastal wetlands and mangroves actually gave a country nothing good; they were a place where mosquitoes spread and where malaria was propagated.

So we embarked on a huge battle, bringing consciousness with a number of NGOs and friends. For a while, we started receiving threats from developers. Not directly from them, but from thugs associated with developers. And we won, as a matter of fact. The morning that we went to meet, the developers never showed up. They chickened out. The next day, it was in all newspapers that the developers were unwilling to debate publicly why they wanted to destroy wetlands.

A couple of weeks ago, a friend sent me a copy of one of the new Mexican peso bills. It has an illustration of a mangrove forest as one of the big assets of the nation. When you’ve fought so hard in order to protect the mangroves, isn’t it beautiful to see them now on the currency as one of the great assets — one of the great values — of the nation? So yes, there is a shift that is happening, but it moves slowly.

In your Natural Numbers video on Mangroves, you list a few ways in which mangroves are being replaced. Is there one leading challenge facing wetlands today or are they still plagued by many enemies?

We demonstrated that every hectare of red mangrove has a value of around $700,000 per hectare. The value is huge. But you will still see developers come in — without asking for any authorization — and cut down red mangroves, and just say, “Oops. I didn’t know. I’ll pay the fee.”

The value of the natural capital in mangrove fisheries alone is around six times higher than the value of the same area converted into a golf course. And you ask, “Then why are we converting them?” Well, it’s an issue of greed and ownership. When one person gets access to that hectare of mangrove and converts it into a golf course, he will actually privatize the income derived from the natural capital and turn it into income for himself. At the same time, removing from the nation an income that is six times larger. It’s the eternal dilemma between what is good for me and what is good for humanity. It is an issue of greed.

Last time we spoke, you said “in popular culture, the idea of a swamp always brings the idea that it’s an evil place that needs to be drained, that needs to be destroyed and changed into something nice, like a golf course”. Have you seen any recent pop culture references to interest people in wetlands?

Yes, there’s a movie starring Salma Hayek called ‘Beatriz at Dinner’ (Watch Trailer). She has been forced to leave her native state in the Pacific Coast of Mexico, the native State of Guerrero, because developers have turned the coastal lagoon — where her family fished and obtained their livelihood — into a hotel.

But what’s interesting is that 20 years ago, if a Hollywood director wanted to represent the raping of land, and the pillaging of third-world ecosystems, they probably would have depicted tropical rainforests and the deforestation in the tropics, like in the Amazon, which is a tragedy by the way. But suddenly, you have a film made in Hollywood in which the emblematic destruction that Western development has brought on tropical countries is the destruction of mangroves and wetlands, which again, shows a huge shift in public perception as to the value of these ecosystems and how important they are for many people. Until not too long ago, everybody knew about the plight of the Amazon, but nobody was concerned about the plight of mangroves.

Also, after Rachel Carson published ‘Silent Spring‘ and a lot of researchers followed her footsteps and we started realizing that organochlorinated pesticides, such as DDT, were actually destroying nature in an amazing way. We all collectively — countries in the United Nations and governments of both developed and developing countries — decided to prohibit the use of DDT. But the World Health Organization put a reservation on the whole agreement, in which they defended the right of the World Health Organization and international programs to keep spraying DDT in coastal lagoons and mangrove forests. And the argument was that we didn’t have any other way of stopping malaria.

Even the United Nations and the World Health Organization, until a few decades ago, were considering that coastal lagoons were places where you could basically wreak environmental havoc and the world wouldn’t suffer. It took us a lot of research on finding out how important they are and what a critically important role these ecosystems play in the environmental balance of a biosphere as a whole.

Note: There’s also a best-selling novel, ‘Where The Crawdads Sing’ by Delia Owens. A coming of age story of a young girl raised by the marshlands of the south in the 50s, soon to be adapted into a film by Reese Witherspoon.

Can you talk about the developing news in Mexico — about the National Institute of Ecology and Climate Change?

It is being shut down; there is a proposal by the President to shut it down. I have already participated in two round tables on the subject. Their argument is there’s nothing that the National Institute of Ecology does that we cannot do in the Ministry of the Environment. As a matter of fact, that is totally contradictory with the reason why the National Institute of Ecology was created.

In the round tables, I mentioned a series of environmental tragedies in Mexico. Basically, the Ministry was so concentrated on dealing with the private developers asking for permits, they were not able to provide good standards for the environment. So, if somebody said, “The air quality in Mexico City is lethal.” The Ministry would say, “No, there is no data. Nobody has measured it. There’s no reason to believe that it’s bad.” And people were falling dead in the streets!

I showed them the infamous satellite image taken by NASA in 1988 of the Mexican Southwest, showing the border with Guatemala and Belize. The deforestation was dramatic; everything had been turned into cattle pasture. The photograph was an international scandal.

We have had an explosion of a pesticide factory that polluted a whole river with at least two million people living in that basin. And the consequences are still visible. It was like the Mexican Chernobyl.

So, at some point, because of international pressure, the President had to accept creating an institute that could actually measure and monitor the environment, independently of pressures from who was in government at that time. A professional institute. There’s not a single country that takes the environment seriously that doesn’t have an independent branch of professionals that can measure environmental quality and give a cry of alarm when things are getting really bad.

That’s truly astonishing! You work so hard with The Tyler Prize to illuminate people and organizations who are helping the environment, and then in other parts of your life, you have this happen. It must be so disheartening to see the world take massive backward steps. How do you stay motivated to fight the good fight?

It is a very difficult time for many of us. I’ve been through so many battles and I have the scars of so many defeats, but also I have the pride — the feather cap — of a few victories. We need to continue working, doing research, and insisting on environmental justice as part of human justice and social justice. A healthy environment is a basic human right. Governments come and go, and hopefully, this approach and this government will end very soon.

But that comes from being an evolutionary biologist by background. If you can understand life on the scale of millions of years, then perhaps a mandate of a president of four or five years doesn’t seem that important. But it’s exhausting. It is really exhausting.

Mexico is known for CONABIO (By Tyler Prize Laureate, José Sarukhán) and so they have the right model. Is the Mexican government preventing ideas like CONABIO from being rolled out widely?

The government hasn’t shut down CONABIO and I don’t think they would dare to because of the prestige it has internationally. But they’re trying to reduce its budget to a minimum. They’re just on total survival mode. The cabinet of the President is doing all they can to shut down CONABIO. It’s very, very sad.

By the way, the short film about CONABIO (It’s Good Business) has been winning lots of awards, and that’s one of the reasons why I think the people in the federal government have not dared to close CONABIO.

Finally, what do you think of the newly announced Laureate, Sir Andy Haines? Why is his work on planetary health such an important area of focus in 2022?

Well, it is very self-explanatory in the context of the pandemic. But he has been particularly articulate in putting together a conceptual framework to understand that social justice is not separated from environmental justice. That it is very difficult to conceive a socially just and fair society if the environment is being destroyed and people are forced to immigrate because they cannot make a living from where they historically earned a living because of environmental destruction. In the same way, we realize with a pandemic, that human health is not separated from environmental health.

We cannot have healthy societies if we don’t have a healthy biosphere. The whole earth is a global ecosystem. And Sir Andy has been particularly good at identifying that much earlier than anybody else, articulating it as a very powerful concept and bringing public attention to it, especially in Europe. So I think the award is extremely well deserved.

Watch the Natural Numbers Episodes here

March 2022

To read more on Dr. Ezcurra’s incredible work:

- Facebook: @ezcurralab.ucriverside

- Ezcurra Lab

- Publications: Exequiel Ezcurra Publications

- Global Research: Dept. of Botany UC Riverside