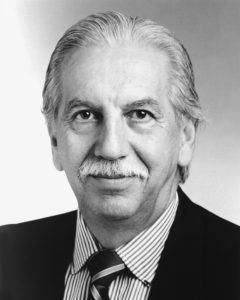

Arturo Gomez-Pompa and Peter H. Raven

Arturo Gomez-Pompa, Professor of Botany and Plant Sciences at the University of California, Riverside, was honored as one of the first voices to draw attention to the problem of rain forest destruction, both in his native Mexico and around the world. As a tropical botanist, he has contributed significantly to the world’s scientific knowledge regarding the plant life of tropical forests.

Arturo Gomez-Pompa, Professor of Botany and Plant Sciences at the University of California, Riverside, was honored as one of the first voices to draw attention to the problem of rain forest destruction, both in his native Mexico and around the world. As a tropical botanist, he has contributed significantly to the world’s scientific knowledge regarding the plant life of tropical forests.

As Mexico’s most prominent voice for forest conservation, Dr. Gomez-Pompa has helped to develop an agenda for reasoned debate on the most effective ways to protect tropical ecosystems; and, as a political adviser, he is credited with leading his governnent toward preserving Mexico’s biological heritage.

His insightful work with indigenous forest peoples – in learning from their knowledge of the lands they inhabit and in focusing attention on the need to involve them in efforts to preserve their environment – is a model for ecologists and agrarian economists worldwide.

As an educator, organizer and institution builder, he has founded a series of institutions that have contributed to basic and applied research, to scientific education, and to public education in tropical botany and biology in general.

At the young age of 24, he was appointed director of a special government commission. The commission, in consultation with the pharmaceutical industry, was set up to survey resources of certain medicinal plants. Expanding the commission’s scope, Dr. Gomez-Pompa presided over a full-scale ecological survey of the Mexican rain forest.

In the late 1960s, when computers were less powerful and more difficult to use than today, Dr. Gomez-Pompa created a botanical database to record information about the plants of Mexico’s Veracruz state. As computers have improved, he has continued to take advantage of their growing capabilities. For example, he recently added images to his botanical database, both as an aid in plant identification and as a way to bring basic information from museums in northern countries back to the developing countries where the botanical specimens originated.

Much of his early research in forest ecology was conducted at one of the institutions he founded – the United Autonomous University of Mexico’s biological station at Los Tuxtlas, in Veracruz state, which has served as a research base for a generation of Mexican and international specialists in tropical forests. Research there provided the raw material for “The Tropical Rain Forest: A Nonrenewable Resource,” an article that Gomez-Pompa and two of his students wrote for the journal Science in 1972. The article has become a heavily cited reference and has served as a catalyst for discussion and research around the globe.

Another institution founded by Dr. Gomez-Pompa is Mexico’s influential National Institute of Biotic Resources. INIREB (from its name in Spanish) has helped establish a new field of research – agroecology, analyzing agricultural techniques used by peoples inhabitiqg the rain forests. The work at INIREB demonstrated that local methods are often based on a profound knowledge of local ecosystems and, in fact, are often better adapted to local conditions than imported techniques. The studies also cast doubt on proposals to use what were called “limitless” tropical resources of sun and soil to grow ill-adapted imported crops.

Based on these ideas, Dr. Gomez-Pompa organized a pilot project, the Maya Sustainability Project, funded by the John D. and Catherine T MacArthur Foundation, leading directly to several efforts in the Mayan regions of southern Mexico. This research has persuaded him that managers of tropical wildermess areas should take into account the knowledge and experience of the region’s indigenous people. He and a colleague first proposed seeking the local people’s advice in defining conservation goals for their region and enlisting their cooperation in implementing those goals.

Gomez-Pompa was effective first as a credible critic of government policies. Later, as his message was heeded, he has actively helped to mold governmental policy. During the administration of President Carlos Salinas de Gortari, his advice led to such government actions as a halt to dam-building activity on the Usumacinta River, the creation of a special conservation district for a threatened porpoise, and the creation of a national biodiversity commission.

Dr. Gomez-Pompa and colleagues organized another nongovernmental organization, the PROAFT A.C., to develop a sustainable-yield forest plan for economically depressed areas of the tropics. The plan, known as PAFT-Mexico, stresses local participation and planning to promote sustainable uses of natural resources and thus improve the quality of life for people who live there.

Now Gomez-Pompa is founding FUNDAREB A.C., an organization to promote the creation of ecological reserves privately owned by local Mexican farmers, individuals, research institutions and corporations. He recently set a personal example by establishing – with his own resources and contributions from friends, relatives and colleagues – a protected area, called El Eden, for research in conservation biology.

Outside of Mexico, he has been influential not solely through his publications and research, but also through his work with the United Nations, including UNESCO’s Man and the Biosphere program, which he chaired. Also he has served on the boards of several international conservancy organizations, including the Nature Conservancy, the World Wildlife Fund and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature.

“He is without question one of the world’s leading botanists, conservation biologists and champions of the tropical forests,” wrote Thomas E. Lovejoy, the Smithsonian Institution’s assistant secretary for environmental and external affairs.

“It is a rare gift that someone with the academic credentials of Dr. Gomez-Pompa has the political and diplomatic skills to put basic ecology into pragmatic resource management programs,” wrote Jean-Michel Cousteau.

Dr. Gomez-Pompa, now a professor of botany and plant sciences at the University of California,Riverside, studied at the Instituto Mexico, the Centro Universitario Mexico, and the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), where he earned a Ph.D. in biology.

Peter H. Raven, Director of the Missouri Botanical Garden and Professor of Botany at Washington University, St. Louis, is being honored for his combination of brilliant botanical research and his efforts to address habitat destruction and species extinction worldwide.

Peter H. Raven, Director of the Missouri Botanical Garden and Professor of Botany at Washington University, St. Louis, is being honored for his combination of brilliant botanical research and his efforts to address habitat destruction and species extinction worldwide.

He has become one of the most effective exponents of the conservation ethic. In every part of the globe where tropical forests still stand, his energetic efforts to preserve habitat and ecosystems have been felt.

Dr. Raven’s early scientific work centered on evolutionary studies of the evening primrose family (the Onagraceae). He was the first in modem times to advance the theory that the chloroplasts and mitochondria, vital structures that occur in living cells, not only represented the remains of symbiotic bacteria but had originated independently on· a number of separate occasions. And his focus (with Brent Heinrich) on energy transactions to explain the characteristics of individual kinds of flowers involved in pollination systems became an influential model for subsequent ecological investigations.

He studied the limitless inventiveness of Onagraceae and other plants in interactions with leaf-devouring insects and other pests. This research led to the formulation, with Stanford colleague Paul Ehrlich, of the theory of coevolution.

According to the theory, living things evolve in concert with one another. Changes in one organism both produce and reflect changes in others. The feeding habits of caterpillars, for example, have greatly influenced plant evolution and, in turn, the evolution of the major groups of butterflies has been greatly influenced by these choices.

The extraordinarily complex ecosystems of tropical forests, with their profusion of species sharing the same environment, offer striking illustrations of the coevolutionary principles that Raven and many biologists are still exploring.

Under Dr. Raven’s leadership at the Missouri Botanical Garden, definitive works on the plant life of major regions of the world (including North America north of Mexico; southern Mexico, Central America; and China thus far) have been organized and the first volumes published. He has written what has become the standard text in botany, as well as influential textbooks in biology and the environment. These are just part of his bibliographic output of 20 books and more than 400 papers.

Since 1971 he has guided the Missouri Botanical Garden on a systematic mission to collect, study and preserve the plants of Latin America and Africa. Under his leadership, the Missouri Botanical Garden has been one of the world’s most effective botanical conservators and a model for institutions of its kind.

Raven has also acted effectively to preserve forests where they stand. As president of the Organization for Tropical Studies, he helped raise funds for several important conservation projects in Costa Rica. As director of the Missouri Botanical Garden, he has strongly supported conservation efforts in Madagascar, Ecuador and elsewhere.

Raven has been equally energetic and effective in finding means to assist the botanical institutions of China and the former Soviet Union, both in their development and in various cooperative research programs. Leading the effort to preserve the remarkable study collections and archives held by the Komarov Botanical Institute, in St. Petersburg, he has been able to raise significant funds to preserve the herbarium/library building and thus to provide the basis for the conservation of the irreplaceable collections that it houses. He has also been deeply concerned with the development of a national capacity to deal with biodiversity in Taiwan, Mexico and elsewhere.

“The National Academy of Sciences, the National Science Foundation, the Organization for Tropical Studies, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, the United Nations Environment Program – all have benefited from his counsel and participation,” wrote William K. Reilly, senior fellow of the World Wildlife Fund. “I think foremost of his successful chairmanship of the Academy of Sciences Committee on Research Priorities in Tropical Biology, which produced a particularly influential report in the late 1970s raising special concern about tropical deforestation.”

“No other individual,” wrote Denver Botanic Garden executive director Richard H. Daley, “has done as much as Peter Raven to bring the importance of the tropical biota to the attention of the world’s leaders, and thereby help create a global movement to protect it.”

“No voice has been clearer or more widely heard,” wrote Raven’s coevolution collaborator, Paul Ehrlich, ”and none more influential. There is no scientist I admire more for a combination of brilliant research and perseverance in trying to make a better world.”

“Dr. Raven is the greatest living botanist,” stated Tyler Laureate Thomas Eisner of Cornell University. “He has addressed, perhaps better than anyone else, the issue of habitat destruction and species extinction. He has become one of the most effective exponents of the conservation ethic.”

Peter Raven was born in Shanghai, China, in 1936. By the age of 14, he was writing monographs on the plants he encountered on Sierra Club expeditions. Later he studied plants more systematically – first at the University of California, Berkeley, and subsequently at UCLA. After postgraduate work at the British Museum, Dr. Raven taught at Stanford University.

In addition to directing the Missouri Botanical Garden, Raven holds the Engelmann Professorship in Botany at Washington University, St. Louis. He has received honorary degrees from 17 universities.

He is Home Secretary of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences and a member of 13 other nations’ scientific academies as well. He is a past member of the National Science Board and a current member of the President’s Committee of Advisers on Science and Technology.

He serves or has served on the editorial boards of 34 different publications, including the journal Scienceand the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

His numerous prizes include the Earth Stewardship Award of UNEP, the international prize in biology of the government of Japan; the Environmental Prize of the Institut de la Vie, Paris; and the Volvo Environmental Prize.